This summer, we began working in earnest with architects, to bring further sophistication to the design of locations in The Witness. Before this time, we had a game that was fully playable, but buildings and the areas around them tended to be placeholders, developed only enough to make the basic gameplay possible. We began working with two architecture firms, FOURM design (for buildings and such), and David Fletcher Studio (for landscape architecture). Both firms are located in the Bay Area, so it's easy for us to meet regularly.

When we sat down to start working with the architects, one of the first things we did was put together a history of the island where The Witness takes place: how long has the island been there? What groups of people lived there, and what kind of structures did they build? How did later civilizations use the structures built by earlier groups?

Quickly we developed a running theme of sites that are old and have over time been used in two or three different ways. When entering a new location, you probably first notice the most basic elements of its structure: where you can walk to easily, versus where you can't; what puzzles or goals are calling for your attention, and what walls or doors might be preventing you from getting to them. If this is all you care about, you can then play through the area in a very utilitarian fashion. But if you have an eye for detail, you may notice the elements of modern construction shoring up the design of an older structure with a different purpose. The design of the new structure tells you something about what the newer guys were doing there, and how it differs from what the older guys were doing there. And if you look really closely, you can see traces of the original footprint of the site (perhaps these are very subtle, some bricks just rising above the dirt in a few places), and infer the purpose of this very old site too.

If you see the different civilizations that came to this island as embodying different philosophies; and you see the structures they built as representative of the way these philosophies led them to interact with the world; and you see further that when they replaced a site, it represents the rejection of some older worldview that they consider no longer useful, then perhaps you start to get some idea of the amount of backstory that can be encoded into the world, nonverbally.

All of this backstory is also directly relevant to the main story -- who you are, why you are on this island, how you may get back home. So, to put it another way, the game is constructed so that the more you pay attention to tiny details during your travels, the more insight you will have to the central story, even though it may not be obvious at any given time what a particular detail has to do with that story.

Having smart architecture, it seems, really helps this process work, brings it alive. If you build a game where people are supposed to pay attention to details, but the details are wrong or naive or just don't have much thought put into them, then at some level the game just won't work. Even if you don't know the first thing about architecture, you have been in enough buildings in your life that the deeper parts of your brain have distilled plenty of patterns about those buildings. Your brain knows the difference between a real building and a nonsense building that wouldn't occur in the real world. It can feel the difference in veracity between carefully-thought-out structural details -- on the one hand -- versus stuff that was just placed by a level designer to look cool. When I showed a recent build to a friend, who had already played an earlier build of the game, he said the new structures made the game feel deeper, more serious.

I was a little surprised by this statement but should not have been, since really, that is what we are aiming for. Thoughtful design of these structures and landscapes gives the game further gravitas.

The most-recent issue of Game Informer printed an article that showed some of the first screenshots of the newly-architected areas appearing in the game engine. It is an interesting article; pick up the issue if you haven't! They also put up a companion article online (but which not as extensive) here:

(Summary article at Game Informer)

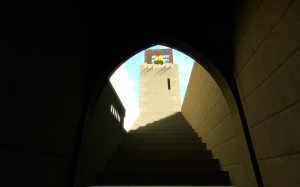

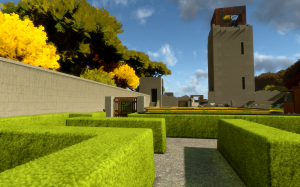

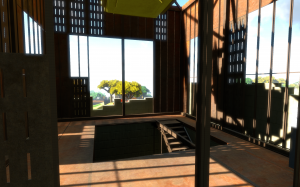

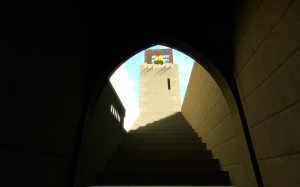

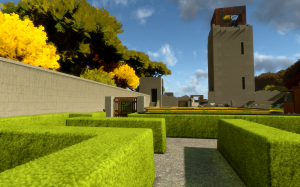

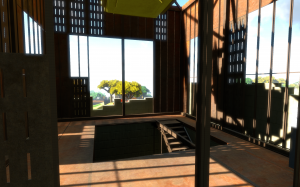

The area featured in this article is the one that we have taken furthest so far in terms of modeling and texturing. Here are some other shots of it:

The Keep, before and after

The Keep, close-up 1

The Keep, close-up 2

The Keep, close-up 3

We've done basic planning for some of the other areas, so I thought it would be nice to show some screenshots of work in progress. For each of these, there's a 'before' version (when we had a fully-playable game, but basic placeholder structures) and after (once we have incorporated the architects' designs, revised the site plans and in some cases even the puzzles, etc):

The Compound, before and after

Glass Factory, before and after

Peninsula, before and after

Vault, before and after

Don't regard these "after" images as representative of what the game will look like! They are still works in progress, and the final game will look substantially better: scenes like these will feel richer due to the placement of detail objects, further care put into the texture mapping and lighting, refinement of the still-rough-drafty terrain features around these structures, and many other bits of subtle game development magic. But I wanted to show these now since they provide a good taste of the game's flavor, and they show how much structural intelligence is brought to the table by working with the architects. Yes, we could have started with the placeholder structures and made them more elaborate and better-looking, in a general video-game-level-design way, but that's different from having well-thought-out ideas subtly embodied in the structures of the areas, which is what we are going for.